Public Interest Technology and Value

The academic view on Public Interest Technologies (PIT) and Public Value (PV)

“Defining of the public interest is always very, very difficult.” - Keir Starmer

This article will draw from the work during my short tenure in my PhD. This work helped me form my thinking around one of the three key pillars for my research into scaling Bitcoin beyond money. In case you haven’t read my first article that details these pillars, you can read it here:

But to cut to the chase, the three pillars are

Bitcoins’ Principles

Public Interest Technologies

Technology Adoption

The following are excerpts from my CoC (Confirmation of Candidature) document. It provides an overview of both Public Value and Public Interest Technologies. They are written for an academic audience, as you will see from the number of references to peer-reviewed literature and the writing style, which differs from the articles I’ve written so far.

Given the work I put in over the year, I thought it would be a waste not to publish this. But I do understand that for the majority of my audience, this will be a very strange article to read. I will follow this up with an article that draws from the literature but is written in a more business-orientated and practical style similar to my previous articles. With that, let’s dive into it

Public Value

The field of public value is tangled in various terms that allude to similar things and referred to as related concepts1. Examples include Public Interest, Public Value, Public Good, Public Realm, Common Good, Civic Interest and Civic Value234. While authors in this field trace its roots back to the time of Greek Philosophers56 its earliest modern introduction appears to be in the 1930’s with Pendleton Herring’s (1936)7 reconciliation theory, followed by Emmette Redford (1954)8 in regulatory administration and Phillip Moneypenny (1953)9 in public administration ethics. The common theme across this work is that it focusses in on public administration as the generator of value for the public.

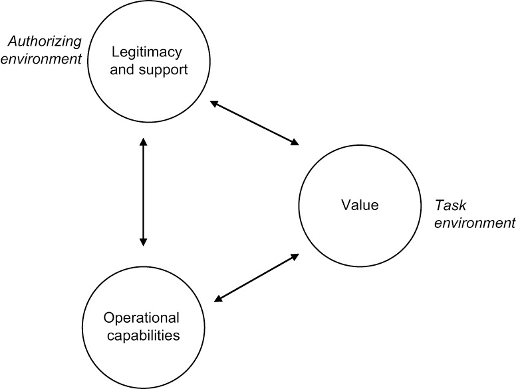

This theme of a public administration centred approach continued with Moore (1995)10 who introduced the strategic triangle framework which was designed to be applied by public sector leadership and management11 via a framework that links three factors shown in figure 2 below

Figure 2. The strategic triangle (Moore, 1995)

Another path of publication is toward Public Interest. This terminology has been criticised in the 1950’s (Bozeman, 2007)12 as the term was seen as imprecise and expansive. However Bozeman (2007)13 goes on to clarify that public interest is about the ideals (Fesler, 1988)14 and that public value has specific and identifiable content. It creates within it a taxonomy that places public interest as an encompassing term with public value as a subset. It is unclear without further review whether this approach has been more widely adopted.

If we look closer at public value, there are many definitions each with their own nuance. First, public value is what the public values15. An alternative definition that builds on this foundation is, public value is what impacts on values about the public16. This definition includes impact given the positive appreciation the word implies as well as shifting the frame away from any one value system. A third definition is, what is created by organisations successfully meeting the needs of citizens17 which introduced the term needs and conflates public and citizens.

From an initial review of the literature there three key elements that need to be considered.

1. The majority of viewed literature centres public value and its associated terms in the context of public administration

2. There may be a taxonomy to the terminology with distinctions between ideals and specifics

3. There are many nuanced definitions of public value.

Public value in the context of this research is a measure to the effectiveness of the Australian third sector digital transformation in executing against their core purpose for the people they serve. Thus, the question of what public value is needs to be more rigorously reviewed with a clear definition of what it is and how it is measured. The three definitions of public value presented by Talbot (2006)18, Meynhardt (2009)19, Church and Mooney (2012)20 show that nuance in this definition can lead to significant difference.

Further as this research looks at public value creation in the Australian third sector, current foundations of public value literature in second sector or government based organisations may present challenges given the difference in organisation characteristics between second and third sector organisations.

In addition, the work of Moore (1995)21 and the strategic triangle could be an element of digital transformation itself through the link of operational capabilities, legitimacy and support, and value which are present in digital transformation. It opens exploration paths on bridging public value for public administration in a broader sector context.

Public Interest Technologies

Public Interest Technologies in comparison to Sociotechnical Systems is a much younger field of study. This term has only just begun to be used in the last decade or so (Schneier, 2022)22 however it’s premise being the potential for technology to meet the needs of civil society (Abbas et al., 2021)23 has been discussed in literature for far longer. This falls under terms like Information Technology and Civic Engagement (Bimber, 2000)24, Civic Technology (Saldivar et al., 2019)25 and Community Informatics (Denison & Johanson, 200726; O’Neil, 200227).

There is still a variability in the definitions surrounding PIT and is dependent on the perspective of the writer and/or researcher. El-Sayad (2021)28 takes the stances that

“PIT is the application of design, data, and delivery to advance the public interest and promote the public good in the digital age” (El-Sayed, 2021)29

This looks to put the emphasis on the outcome of public interest as the primary goal within the environment being the digital age.

In contrast the Social Innovation and Research Institute (SIRI) at Swinburne University defines it as

“Public interest technologies serve to address social challenges and advance the public or common good. Public interest technologies put people and society at the centre of our technological choices and strive to ensure that the benefits of technology are widely shared” (Swinburne University of Technology, 2022)30

This definition on puts focus on the technology choices primarily determined by public interest as the primary element and how it can be used to deliver common good.

And finally New America (2002)31 define it as

“At its heart, public interest technology means putting people at the center of the policymaking process — not just by designing programs with constituents’ needs in mind, but by engaging directly with constituents throughout the policy design and implementation process.”

This definition looks to remove the focus from technology and prioritise its application in public policy through the co-creation of solutions with citizens.

These differences in conjunction with the infancy of this field highlight an inconsistent understanding and no consistent interpretation of what PIT is. If we approach the terminology with a broader lens we can see that the words Public Interest have been used consistently across other domains like co-design, engagement, engineering and consulting (Abbas et al., 2021)32.

While this field of study is fluid in its definition any advances in this field will provide a frame of reference on the convergence of public interest, public value and technology with common terminology that should be adopted to align to new contributions in this field.

Conclusion

This was meant to provide an academic view of this field, and when you compare it to my previous posts, you will see the difference in style. I’ve always respected academia, as they bring a research rigour that is sorely missing in business today. I aim to bring some of this to business to help strike a better balance between the academic process and business practicality so that we can all achieve better outcomes.

In my next article, I will bring the above to life in a practical context. I will lean on two of my Bitcoin principles, simplicity and meritocracy, to show how the above can be applied practically as one of my three pillars for my ongoing research.

If you’ve enjoyed reading these articles, I would love for you to subscribe below. It will help me expand the reach of this publication and, hopefully, turn this into a full-time career.

Thanks, and see you in the next one.

Benington, J., & Moore, M. (2010). Public value: Theory and practice. Bloomsbury Publishing

Benington, J., & Moore, M. (2010). Public value: Theory and practice. Bloomsbury Publishing

Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

Lilla, M. (1985). What is the civic interest? The Public Interest, 81, 64.

Benington, J., & Moore, M. (2010). Public value: Theory and practice. Bloomsbury Publishing

Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

Herring, E. Pendleton, Public Administration and the Public Interest (New York, 1936), p. 9

Redford ES. The Protection of the Public Interest with Special Reference to Administrative Regulation. American Political Science Review. 1954;48(4):1103-1113. doi:10.2307/1951013

Moneypenny, P. 1953. “A Code of Ethics as A Means of Controlling Administrative Conduct.” Public Administration Review 15 (3): 185–187.

Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard university press.

Alford, J., & O'Flynn, J. (2009). Making Sense of Public Value: Concepts, Critiques and Emergent Meanings. International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 171-191.

Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

Bozeman, B. (2007). Public values and public interest: Counterbalancing economic individualism. Georgetown University Press.

Fesler, J. W. (1988). The State and Its Study The Whole and the Parts: The Third Annual John Gaus Lecture. PS: Political Science & Politics, 21(4), 891-901

Talbot, C. (2006). Paradoxes and prospects of ‘public value’. Public Money & Management, 31(1), 27-34.

Meynhardt, T. (2009). Public Value Inside: What is Public Value Creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 192-219.

Church, L., & Moloney, M. (2012, 24-27 July 2012). Public Value Provision: A Design Theory for Public E-services. 2012 Annual SRII Global Conference,

Talbot, C. (2006). Paradoxes and prospects of ‘public value’. Public Money & Management, 31(1), 27-34.

Meynhardt, T. (2009). Public Value Inside: What is Public Value Creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3-4), 192-219.

Church, L., & Moloney, M. (2012, 24-27 July 2012). Public Value Provision: A Design Theory for Public E-services. 2012 Annual SRII Global Conference

Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard university press.

Schneier, B. (2022). Public-Interest Technology Resources. https://public-interest-tech.com

Abbas, R., Hamdoun, S., Abu-Ghazaleh, J., Chhetri, N., Chhetri, N., & Michael, K. (2021). Co-Designing the Future With Public Interest Technology. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 40(3), 10-15.

Bimber, B. (2000). The study of information technology and civic engagement. Political Communication, 17(4), 329-333

Saldivar, J., Parra, C., Alcaraz, M., Arteta, R., & Cernuzzi, L. (2019). Civic technology for social innovation. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 28(1), 169-207.

Denison, T., & Johanson, G. (2007). Surveys of the use of information and communications technologies by community-based organisations. J. Community Informatics, 3.

O’Neil, D. (2002). Assessing community informatics: A review of methodological approaches for evaluating community networks and community technology centers. Internet Research

El-Sayed, S. (2021). Power to the Public: The Promise of Public Interest Technology. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 8(3), 478-481.

El-Sayed, S. (2021). Power to the Public: The Promise of Public Interest Technology. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 8(3), 478-481.

Swinburne University of Technology. (2022). Public Interest Technology. https://www.swinburne.edu.au/research/institutes/social-innovation/public-interest-technology/

New America. (2022). Public Interest Technology. Retrieved 29/04/2022 from https://www.newamerica.org/pit/about/

Abbas, R., Hamdoun, S., Abu-Ghazaleh, J., Chhetri, N., Chhetri, N., & Michael, K. (2021). Co-Designing the Future With Public Interest Technology. IEEE Technology and Society Magazine, 40(3), 10-15.